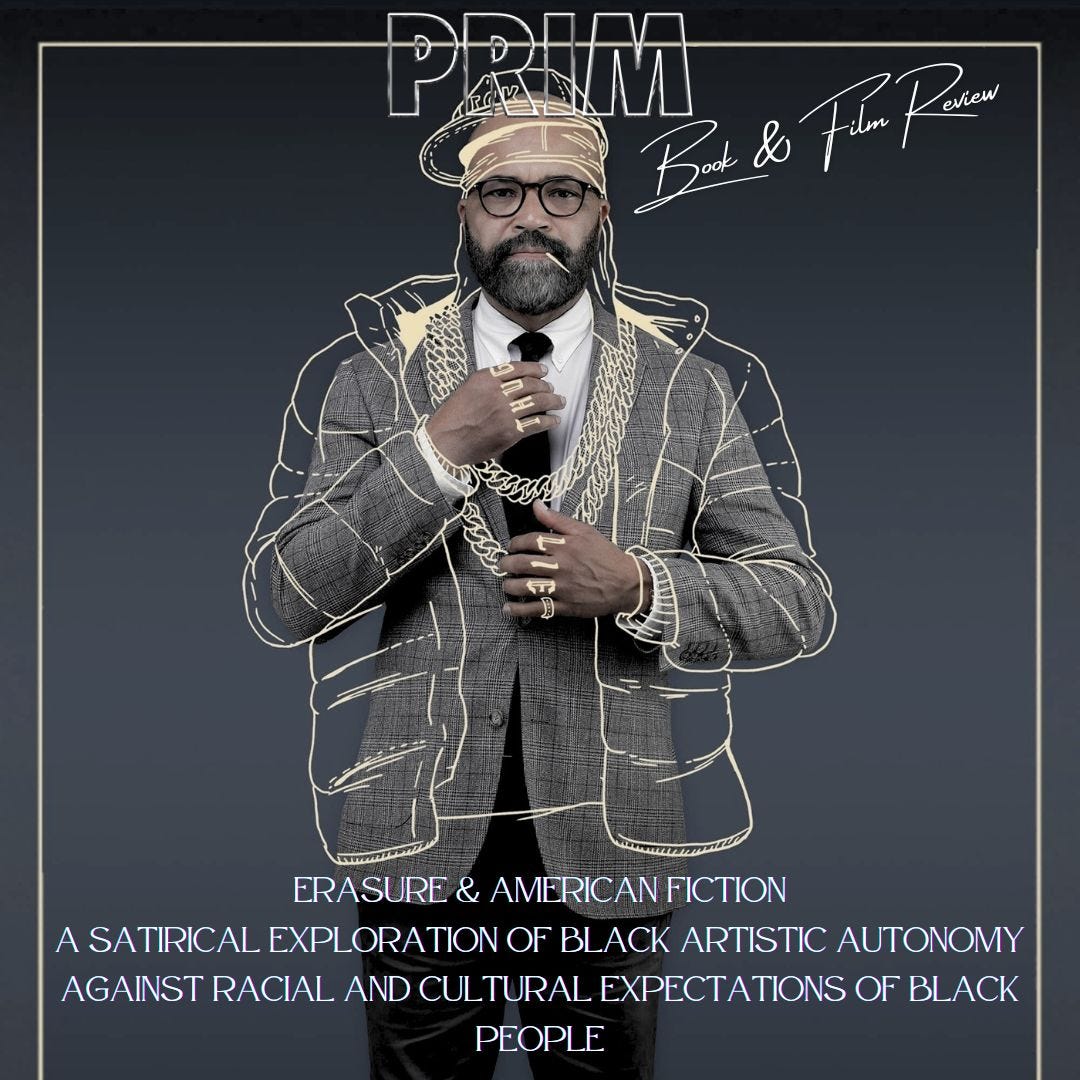

Book & Film Review: Erasure/American Fiction

Memuna Konteh skillfully dissects the pages of 'Erasure' and the subsequent cinematic adaptation 'American Fiction' with a keen eye for contextual irony and a touch of comedic prose.

An insightful exploration of the modern classic ‘Erasure’ and its 2023 film adaptation ‘American fiction’ that satirically illustrates race and cultural expectations of Black people in today’s America.Taking a personal and critical reflection on Black art’s autonomy beyond the influence of the white gaze.

By Memuna Konteh

“Everyone else breaks the rules, so why not [us]?.”

Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison, the lead character in Percival Everett’s Erasure and its movie adaptation, American Fiction, speaks to me on every page and in every frame. He is my inner tortured artist, literary critic, linguistic enthusiast, misunderstood middle child, socially anxious adult, and so much more. I read much of the novel curled up on the sofa, savouring every sentence, ruminating on the footnotes of Monk’s essays, and sounding out the staccatos of AAVE dialogue in his parody piece My Pafology/ Fuck. I was satisfied there could be no better way to take in this rich and complex narrative, essentially two novels in one, that converse with each other in a hilariously tragic way about what it means to be authentic, successful, and free as a creative* Black person. Imagine my surprise when, seated in a cinema in York, surrounded solely by white people (eating my contraband rice and stew), my enjoyment of the story peaked once more.

In my opinion, adapting books for the screen is a delicate dance, best executed when the book’s author acts as the lead choreographer. Percival Everett’s work on American Fiction rivals Stephen King’s many iconic adaptations, as it amplifies the original story through a masterful use of techniques unique to film. From the casting choices to scoring, wardrobe selection and the updated location and time period, with meticulous attention to detail, resulting in a book-movie combo that perfectly complements each other.

“Seeking acceptance into a radically Black literary zeitgeist that probably doesn’t exist.”

Despite its irreverent tone, both iterations of the story left me deeping many things, particularly my art, as an expression of my Blackness. Like Monk, I don’t believe in race theoretically, yet I feel compelled to create work that is rooted in my ethnic identity as a Sierra Leonean, Mende immigrant, and reflects my social standing as a working-class Black Brit. Erasure and American Fiction made me question my motivations:the extent to which I’m pandering to the white gaze and expectations of industry gatekeepers, and conversely, whether I’m seeking acceptance into a radically Black literary zeitgeist that probably doesn’t exist.

“Erasure, American Fiction, and My Pafology/ Fuck are ridiculous riddles, possessing the kind of biting universal humour born of generational trauma.”

My main takeaway from Monk’s journey, however, is that our best work emerges when we detach from such existential questions and take ourselves less seriously. At their core, Erasure, American Fiction, and My Pafology/ Fuck are ridiculous riddles, possessing the kind of biting universal humour born of generational trauma. We laugh, cry, and cry laughing, walking away from the story confused and slightly saddened but lighter for it- much like a visit from our favourite drunk uncle or bitter aunt (who has a tendency to air the family tea at the worst possible moment).

The award nominations, (and wins in the Novel’s case), are cherries on a moreish cake of poetic irony. While Sterling K. Brown deserved all the Oscars simply for blessing us with all that bawdy in batty-riders, one entirely misses the point if one believes recognition from an academy or institution holds any significance to this type of art. Art is already in celebration of itself, embracing both the stereotypical and nuanced aspects of the cannon upon which it builds, and, most importantly, of the beautiful contradictions of Black life:

In the words of Van Go Jenkins, the protagonist in Fuck, “Everyone else breaks the rules, so why not [us]?”