Book Review: In The Ditch by Buchi Emecheta

Sameerah Balogun revisits Buchi's autobiographical novel first published in 1972.

A review of Buchi Emecheta’s novel In The Ditch. A story of welfare, class and the harsh realities of 1960s - 70s Britain.

by Sameerah Balogun

‘Two sides to every coin’ becomes painfully apparent in Buchi Emecheta’s In the Ditch (1972), in which the Nigerian main character Adah Obi watches as her dream of a better life in the United Kingdom turns into a nightmare.

Set in the beginning of the 1960s, the semi-autobiographical novel tells the story of Emecheta's alter-ego heroine, who came from Lagos to London as a young, educated mother of five just to end up in the welfare system. At the bottom of the social hierarchy, she finds herself having to deal with the interwoven intricacies of racism, sexism, classism, and poverty, turning her from an elite in her home country to a second-class citizen in the Western World.

The post-war efforts of decolonisation and the dismantling of the British Empire brought a change in the UK's immigration policy, not only allowing people from Commonwealth countries to immigrate for labour but also concomitantly creating the ghettoization of bigger cities, leading to housing crises and the formation of overcrowded slums, one of which Adah and her five children lived in North London. At the beginning of the novel, they move from a rat and cockroach-infested accommodation with no electricity but a ‘juju’ landlord into the Pussy Cat Mansions, a council estate in Kentish Town which Emecheta compares to a prison “of red bricks with tiny yellow windows” and around 140 flats accessible by dangerous steep steps full of rubbish and a “thick lavatorial stink”. Leaving a cramped single “half-bedroom” and her abusive husband behind, Adah started anew in a damp flat with cupboards carpeted in mildew, having “no beds, no curtains and no floor coverings” during the first night but “her independence, her freedom, and peace of mind” – even if that meant to go from one dehumanising living condition into the next.

“Because of my blackness and because I was alone and because I was young and because I had five children all under 6, I was given one of the worst flats imaginable in the whole of London”, said Emecheta in The Light of Experience BBC talk in 1983, as she reflects on the first few years after she arrives in the UK at 18-years-old. In an interview with Cover to Cover later that same year, the author reveals upon her arrival in Britain, she became aware that her place in society was not only determined by her gender but the colour of her skin. “She was beginning to learn that her colour was something she was supposed to be ashamed of”. In the past, she was naively convinced that “going to the United Kingdom must surely be like paying God a visit”, she came to the quick realisation that it better resembled stepping onto the devil’s grounds. “If Adah had been Jesus, she would have passed England by without a blessing”.

Through Adah, Emecheta tells not only her own peculiar story as an immigrant in the UK but simultaneously sheds light on those with a similar journey. Whether forced or fortunate enough to leave their home country in pursuit of better opportunities in the, oftentimes, glorified West. Only to be brought to their knees by racialization and its internalisation within societal systems, displacing highly educated people in low-income jobs if they are fortunate enough to break through the barriers in the first place. That was, in the past, a pertinent issue for the Windrush Generation in the UK as it remains with immigrants in the global west at large today.

“If Adah had been Jesus, she would have passed England by without a blessing”.

Although the British government introduced the Race Relations Act in 1965, it didn't take away the difficulties caused by intersectional oppression that Emecheta lays out in her novel. As Adah was the sole caretaker of her children, she was forced to quit her job as a librarian at the British Museum, becoming entirely dependent on the government dole and putting her fortunate future on hold. "Her socialisation was complete. She, an African woman with five children and no husband, no job, and no future, was just like most of her neighbours — shiftless, rootless, with no rightful claim to anything". And this is without an explanation of its reasoning nor any control over the matter of fact.

Through Adah having to live in a place like the Mansions and thus being labelled as a "problem family", the struggles faced by not only single mothers in general but particularly those of colour within Western societies are ultimately shown. In her own definition "A family is a problem one if, first, you're a coloured family sandwiched between two white ones; secondly, if you have more than four children, whatever your income is; thirdly, if you are an unmarried, separated, divorced or widowed mother, with a million pound in the bank, you are still a problem family and lastly, if you are on the Ministry you are a problem". Her position in society does not detract from her awareness of its goings-on not only on a personal but, due to her status as a sociology student, also on an intellectual level.

Instead of being confined to the chokehold of archetypes, Adah is determined to fight for her freedom, come what may. As Emecheta’s second novel, Second-Class Citizen unveils in-depth Adah had – despite all odds – managed to receive an education at a colonial missionary school, defining her fate as a member of the middle-class elite instead of being a servant in her uncle's house as the fate of most Igbo orphaned girls after their father dies. She had dreams of becoming a writer and she most certainly would be. Even if the stepping stone to heaven was to marry, and finance an insipid husband and his family while fulfilling her duties as wife. So as she had fought in Nigeria, she would have to fight in the UK. "It was either to do that or to perish". Since she had sold everything for her education, there was no going back.

Thus, the reader follows along as Adah fights and without the help of any "fancy men" – as patriarchy loves to suggest – but on her own, empowered by friends she had made in the ditch, with whom she "found joy in communal sorrow". After all, everyone in the working-class trenches was sitting in the same boat of dependency, irrespective of inner group differences. Joining the group of ditch-dwellers, Adah slowly but surely learns how to conform to the expectations of a woman with her positionality, giving her a role to perform in which she ultimately finds security. Even if that meant the silent acceptance of racism for the sake of peace. Adah's journey within the novel becomes more than a social commentary on African womanhood but also the development of double consciousness and its influence on the performance of identity as part of the diaspora.

Navigating her newfound role while being at the crossroads of tradition and modernisation. Adah's condition becomes a balancing act between a sense of pride, a fear of the unknown, and the agency of liberation and freedom.

Her resilience motivated her to overcome the coldest winters in the ditch and eventually resurge in a maisonette "match-box" close to Regent's Park, as the government made efforts to improve housing. Working-class people ended up in more expensive middle-class areas, where there were no clothes exchanges nor the same comfort of community that had existed in Queens Crescent. Adah nevertheless managed to re-embark on her dream of finding liberation through writing.

“She became the first female novelist, who not only conveyed the gendered experience of what it meant to be Black in post-war Britain but also shed light on its working class.”

Buchi Emecheta’s In the Ditch was originally published as a column of “observations” in The New Statesman, which eventually turned into a book, followed by the aforementioned ethnography, Second-Class-Citizen, which is both a sequel and prequel. Including The Bride Price, the initial manuscript of which was burned by her husband. These works are among the over 20 books she wrote in her lifetime. She became the first female novelist, who not only conveyed the gendered experience of what it meant to be Black in post-war Britain but also shed light on its working class. However, she did not consider herself a feminist. As she said herself, “If I am now a feminist, I am a reluctant feminist or a feminist with a small f.", justified by the mere fictionalisation of her lived experiences. While she was trying to make sense of her life through words, she addressed injustices faced by Igbo women in Nigeria and African women at large. For her, writing not only brought liberation to herself but also paved the way for those alike who would come after her.

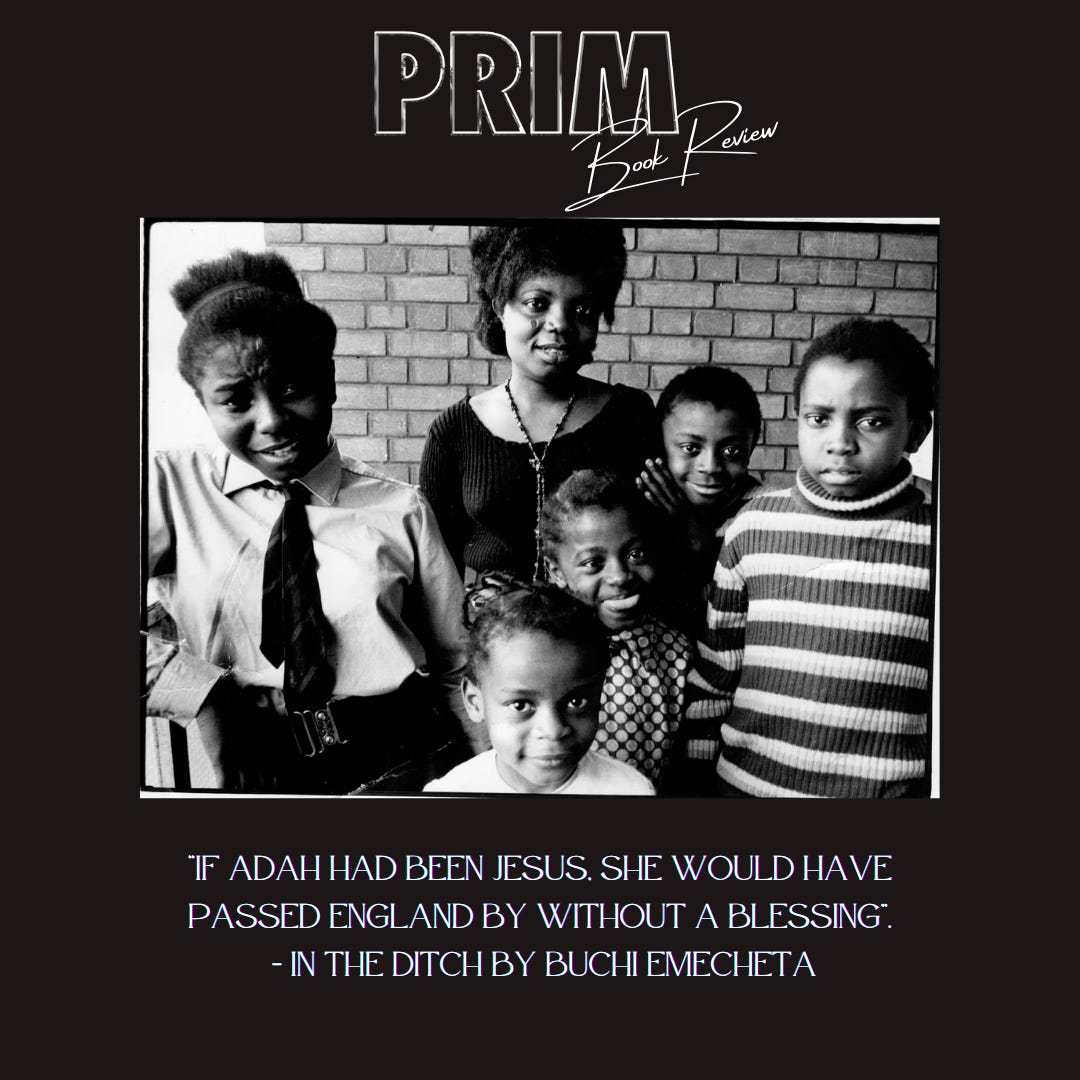

Buchi Emecheta with her family in 1972, Photograph: Sylvester Onwordi