Film Review: SHAKEDOWN

Dkéama Alexis takes us back down memory lane of Weinraub's portrayal of a bygone moment wherein the Black lesbian community and commerce intertwined.

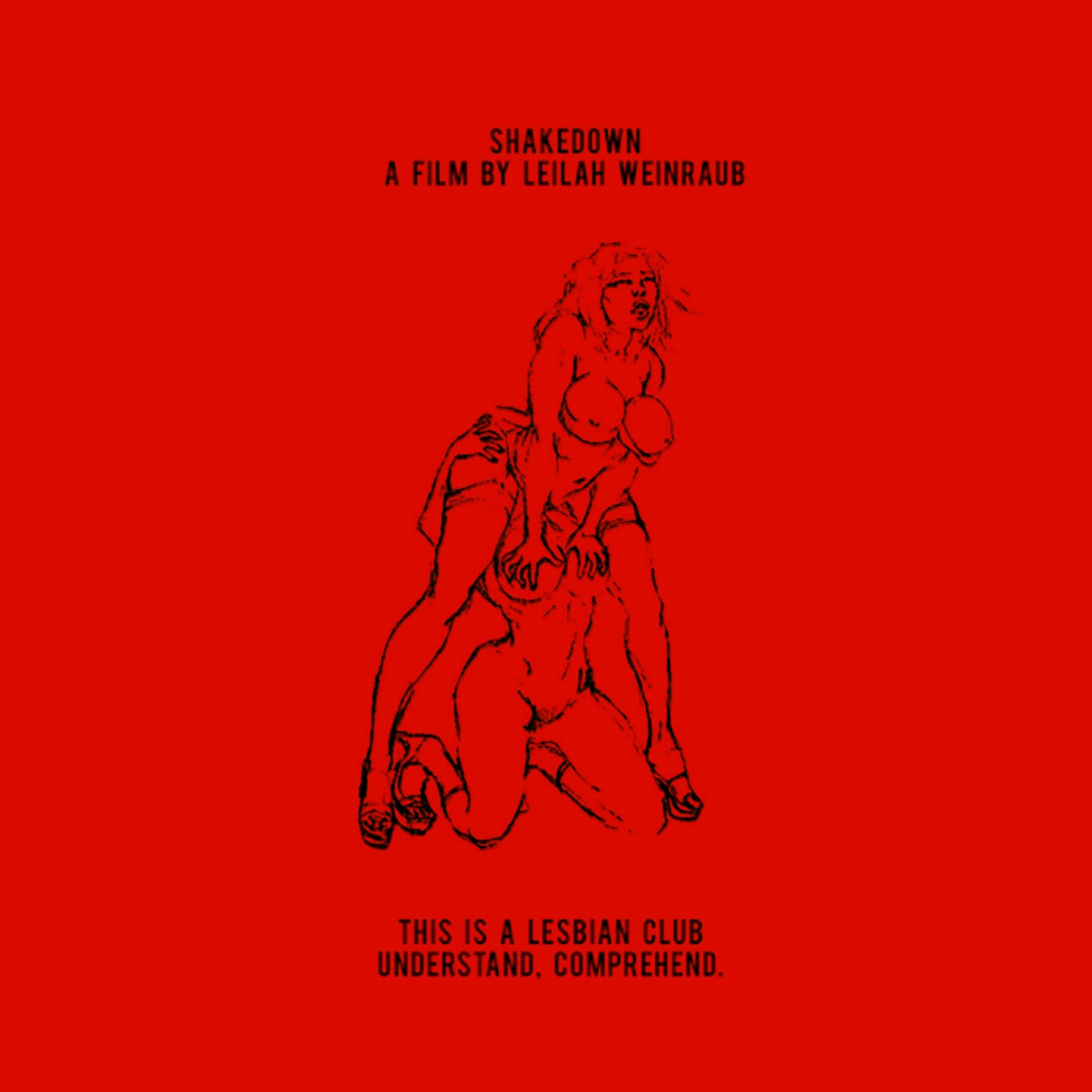

A review of Leilah Weinraub's carefully crafted documentary SHAKEDOWN which unveils the eponymous Black lesbian strip club that ran from the late 1990s to the early 2000s in Los Angeles, CA.

by Dkéama Alexis

Leilah Weinraub's carefully crafted documentary SHAKEDOWN unveils the eponymous Black lesbian strip club that ran from the late 1990s to the early 2000s in Los Angeles, CA. A luminous marvel of Black lesbian eroticism, performance, and space-making, the Shakedown Club was an autonomous realm where dancers (called Angels) could re/invent themselves, stoke desire, and make a living. Weaving together talking-head interviews, recorded dances, offstage footage, and snapshots of DIY flyers, Weinraub portrays a kaleidoscopic memory of a bygone moment wherein the Black lesbian community and commerce intertwined.

“SHAKEDOWN does not showcase sex simply for the sake of spectacle. It is an archival vessel for self-interrogation.”

SHAKEDOWN does not showcase sex simply for the sake of spectacle. It is an archival vessel for self-interrogation. Just like the breathless audiences packing the circle all those years ago, viewers of this 70-minute film must maintain a compassionate and unflinching gaze to fully witness the Shakedown Angels in the lucrative midst of their erotic self-possession. Weinraub wanted to "follow the dollar to trace the community, and how they work together," maintaining labour as the most salient throughline from the palms of the clubgoers to the pockets of the dancers. In a voiceover right before the 4-minute mark, I-Dallas gives a firm directive while the last of the flyers flash across the screen: "If you straight you don't need to be in the front. Period. if you not gon' tip and you straight, you don't need to be in the front. but don't disrespect by moving out the way when somebody performing they show. Thank you." This, a clear orchestration of clientele to remind them exactly who (and what) Shakedown was for. One must be mindful when partaking in the gritty, shimmering display of dancers in all their glory as they command the attention of attendees with tantalising floorwork and lap dances.

Nudity and sexual play undeniably take centre stage, but these elements are amplified by nuanced, intimate reflections from some of Shakedown's major players who make visible and vocalise the mechanics and unbreakable lineages of local Black queer performance. Enter Miss Mahogany, the OG Angel: mother-mentor to many who muses on her ascension within LA's nightlife spaces, like the famed Jewel's Catch One, as well as her transmission of knowledge regarding the delicate practice of fueling fantasy for lesbian clubgoers. She inspired her "gay lesbian son" Ronnie Ron to start Shakedown, and Ronnie took the helm as the charismatic CEO and MC, responsible for setting the stage by working the lights along with the crowds. Of course, there's Egypt, a de facto Shakedown legend who asynchronously permeates the documentary.

Footage from inside the club starts with her as she ruminates on the freedom and fluidity she experienced with her persona. Weinraub shows her in her zone, mixing the hard with the soft, moving through fast-paced choreography while draped in lush pink lingerie, a captivating shot, well-matched to her self-assured words: "I can do whatever I wanna do. Nobody fucks with Egypt." By carefully peeling back the layers of this itinerant h(e)aven, Weinraub also permits a glimpse into the evocative malleability of identity and presentation, from Slim's insights on her gender-transgressive performances to Ronnie's recount of entering the underground lesbian scene as an aggressive femme who later "became a stud image." Deliciously varied are the convergences and contradictions of Black lesbian being, and SHAKEDOWN allows onlookers to lavish in these complexities, rather than attempt their reconciliation.

“Fifty-three minutes in, Weinraub presents a freeze frame of someone throwing a handful of ones at Jazmyne…”

In a world governed by capital, Shakedown was a rare microcosm where currency was largely dictated by the intentions and needs of Black lesbians. Unfortunately, worlds governed by capital enforce their norms by dispatching agents of the state to do their bidding. A b-roll shot of a helicopter gliding across an orange sky appears on the heels of Ronnie sharing her dreams of lifting Shakedown out of the underground into its building, an editing choice that visually connotes the incoming spectre of surveillance. Following the dollar brings viewers to an unexpected point of unravelling in the club's decadent allure. Fifty-three minutes in, Weinraub presents a freeze frame of someone throwing a handful of ones at Jazmyne, the money hanging in the balance for several seconds before the scene continues and police officers enter the frame to whisk her away for solicitation. Their sudden arrival serves as a sudden, visceral reminder that the homes marginalised people make for ourselves are often revealed to be more fragile than we can ever anticipate. Continued state interference hastened Shakedown's demise, and just like that, heaven came crashing down because the ecstatic Black lesbian is a threat to the social order.

Mirroring the reactions of both club staff and clientele to the end of Shakedown—some blasé, some bitter, some coolly aspirational—Weinraub closes the film in a way that refuses nostalgia or oversimplifications. Egypt's words are the last heard in the film, recorded some years after Shakedown's shutdown: "Everything comes to an end at some point." What to make of this matter-of-fact admission, especially almost two decades past the Shakedown era? One can look towards Weinraub's subsequent efforts to independently produce and distribute the film as a testament to the very same impermanence, meticulous labour, and relegation of complex Black lesbian storytelling to the marginal realm of excess that she chronicled with her camera. Once finished, SHAKEDOWN found wider release in a time when a growing wave of anti-Black police violence, gentrification, and anti-queer sentiment saturated the so-called United States. Weinraub's invitation to interact with this potent sliver of Black lesbian survival, pleasure, and expression also empowers audiences to consider current-day possibilities, regardless of what's at stake. Gems resembling Shakedown may very well exist underground right now, rough-hewn yet still prismatic in effect. Should they be unearthed, may those hands and eyes do so as thoughtfully as Weinraub did, preserving the material so that it can cast its precious and colourful light as far as it wishes.

been thinking abt this endlessly “ the ecstatic Black lesbian is a threat to the social order.” thank you for this review